After a 4-1 defeat at the weekend, suffice to say the Monday feeling we have this week isn’t the same as last week’s elation. Now it is time to go through the tactics employed at Southampton and look at why they didn’t work for Aston Villa. Some of this will require looking at statistics, some asking people to contemplate ideas but, as a whole, hopefully it should provide some insight into why we came away with nothing.

Never underestimate a team

I highlighted the potential of Nathaniel Clyne and Gaston Ramirez before the match, and suggested that Villa needed to keep close control over the pair due to their ability to supply the ball. It’s a simple logic – cut the supply and the end product stops – but it works. Sadly Villa didn’t do this and paid the price.

Keep it simple, stupid

There’s an old saying in business which goes under the acronym K.I.S.S. and, as the header above indicated, it stands for keep it simple, stupid. What does this have to do with the game? Looking at Barry Bannan’s passing statistics as an example, the diminutive Scottish player had a 63% completion rate for passes. Of his thirty passes, Bannan completed 17 of 23 short passes, and a mere two of seven long passes.

Of Bannan’s long passes, one of the completed passes was a back pass to the keeper, meaning only one of his long passes, something he is beginning to develop a reputation for, actually reached the target. Bannan was therefore left with a 28.6% completion rate for long balls. The simple fact of this matter – long balls don’t work most of the time, and he needs to stop trying them.

If we take a step back and look at Bannan’s passing against Swansea, Bannan had a 64% total pass completion rate, but a woeful 20% completion rate for long passes completing just one of five passes. Against Newcastle, Bannan again completed just one long pass, thankfully out of only three attempted. What is it going to take to illustrate to Bannan that these passes cause more issues than they solve? Keep them short.

As I’ve said numerous times before, the ball will travel faster than a player if it is played properly, with speed, between two points. Look at the Spain team and you’ll see that the player on the ball doesn’t generally have to move, rather their team mates will move around to give them outlets.

Consistency, my friends, is a necessity at this level

After a fairly stark analysis of why Bannan’s long passes are yielding nothing much, I want to turn my sights to Ciaran Clark. Clark needs to improve his game-to-game performance as his statistics against Southampton paint a poor picture.

Of a total of three tackles, Clark was successful with just one. For a defender, one has to ask if that is good enough. For me, it’s not so much that he only had to make three tackles – that could be valid for a number of reasons – rather that he only completed 33.3% of them. Short fact – not good enough.

I don’t want to slide all the blame on to the young players because poor managerial decisions have meant their careers have been stunted. The fact is that, in the past, the youth have not been developed as they should have been – no manager developed the youth for a variety of reasons from a lack of interest in loaning players out (Martin O’Neill) to a simple lack of options due to a small squad (Gerard Houllier and Alex McLeish).

It’s time to see what has changed, and what has stayed the same

If we look at the arc that the club have been travelling along over the past few years, we will see that some things are variable, and some are fixed. Looking at last season, people were eager to put everything on the shoulders of McLeish, blaming him continuously for every mistake at the club, leaving the players largely free from blame. Every long ball that was punted by a player was obviously a direction of the manager and, as per the old saying in football, it was the manager losing games and the players winning them.

Now that it’s fully evident that Paul Lambert is not telling balls to punt the ball long, fans need to use a critical eye and ask why they are still being pumped long. Whilst doing that, they need to also question if their view of McLeish was tainted by the use of him as a catch-all blame vehicle – the evidence on player performance seems to illustrate that whilst McLeish was far from faultless, he may well have been shouldering the blame for many players unfairly.

Graphical analysis

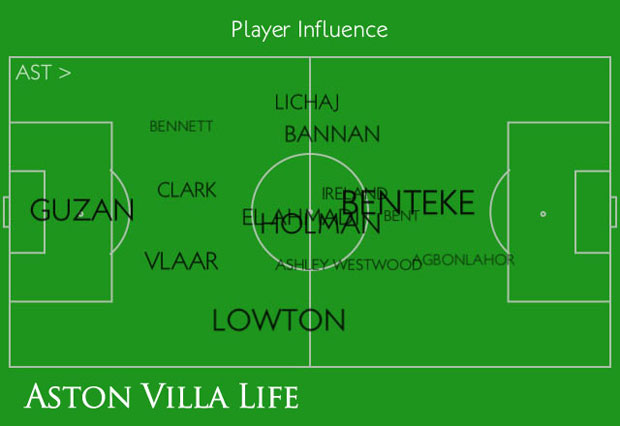

Getting back to the analysis of the here-and-now, I wanted to illustrate where issues were occurring by showing Villa’s overall influence on the pitch. As per the usual influence analyses, the size of the player name indicates the impact of that particular individual on the game, whilst the position of the name indicates the player’s average position.

By looking at Villa’s graphic, we can see that both starting full backs were pushed forwards leaving big gaps behind them. Whilst it’s important for the defence to push up, if they don’t move as a unit, it does mean there are areas to be exploited by the opposition. With Joe Bennett coming on as a replacement for Eric Lichaj, his placement was more in line with a flat back four.

This kind of variation in the defence could mean one of two things – either the defence was totally out of shape, or that it was retreating backwards into a flat back four as the game went on. In reality, it was a bit of both, the lack of shape coming from panic where key players illustrated above started to play poor passes or take the wrong position.

In the above influence graphic, look how wide Bannan appears. Brett Holman is almost central despite needing to cover the right side. Ireland and El-Ahmadi are squashed together leaving Matthew Lowton as the only player wide on Villa’s right, despite having to deal with an opposing full back and left midfielder – a two-on-one situation that was replicated repeatedly due to poor Villa movement.

Push forward or stay back? Villa’s defence often didn’t know which way to turn

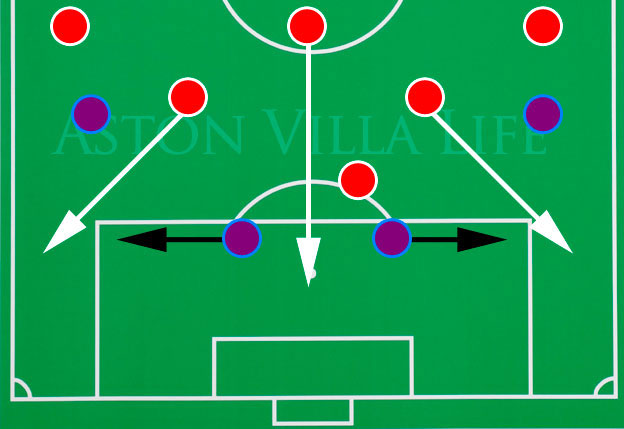

If full backs push forwards against a team with five in the middle, they come up against an opposing team’s wide midfielders. This leaves gaps that are easily exploited by diagonal passes from wide areas where Adam Lallana and Jason Puncheon can get at the Villa defence or, in ideal circumstances for Southampton, get past the full backs leaving the Villa centre of defence in danger of being split in half.

Packing five in the middle isn’t a particularly hard to do tactic, and can offer sheer numbers against an opposition four. When you consider that Villa’s midfield is narrow, any wide player with pace that is backed up with a defender, then gives Villa a two to one advantage.

For example, Eric Lichaj would have had both Jason Puncheon and Nathaniel Clyne coming at him. It’s an obvious statement to say that Lichaj can’t mark two players and, coupled with poor passing from Villa’s midfield, this meant that possession was ceded to Southampton and attacks in wide positions would cause issues. Due to this two-to-one advantage, Clyne was able to roam into the centre making Southampton’s midfield even more packed with players.

The influence graphic in the last section also shows how Bannan was pulled wide dealing with this two-to-one advantage as we look at his average position, and how Holman was pulled into an almost central role for the same reason.

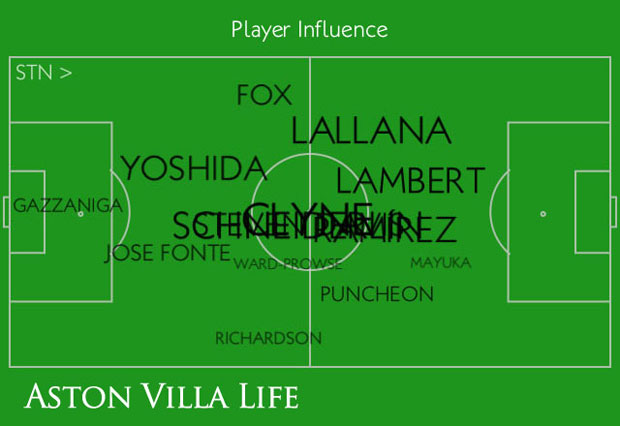

By comparison, look at Southampton’s influence below and you will see that Daniel Fox and Adam Lallana have a free reign against Matthew Lowton. As per the above example with Lichaj, Lowton can’t mark two people, forcing the central defence to split in half, which causes obvious issues.

Here are the variations that cause issues:

Defensive positioning and how both shapes cause problems

In the above graphic, the previously mentioned number advantage is illustrated – the full backs are pushing forwards, but there is an extra man advantage in the midfield area.

In the second variation shown above (where Villa retreat into a flat-back-four), Ron Vlaar (marked as RV) is unable to mark three players. In a situation where the defence are displaying issues with both positioning and retention, Vlaar will have to try and deal with Steven Davis, Gaston Ramirez, and Rickie Lambert – it’s clearly not possible for Vlaar to be able to close three outlets simultaneously – one could argue that this contributed to his frustrations later in the match.

As well as this, because the Villa midfield didn’t operate effectively, was passing wildly, giving away possession, and otherwise not closing players down, the five in Southampton’s midfield became a swarm of players that the defence simply could not handle. Five players is enough for most midfields to contend with regardless of performance but, as we have seen from the influence graphic, the five in the middle pulled players totally out of position – Bannan and Holman were both operating in distinctly different areas to which their formation dictated.

So, a combination of poor positioning, lack of confidence, and inability to pass the ball well enough caused Villa the issues that led to their 4-1 defeat. Will we learn from the lessons? What do you think contributed to the result?

As per user request – total passing graphics

Please see below the total passing for Aston Villa:

And the total passing for Southampton:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download