It’s Monday morning and time to use some hard facts to understand the tactical reasons we lost the game against West Ham. On the face of it, there could be a multitude of reasons attributed – maybe it was a new team working together for the first time under pressure, maybe it was down to the heat, maybe it was down to x or y.

However, I wanted to drill down into some of the pertinent statistics that illustrate graphically why Aston Villa didn’t get off to the best of starts.

To give a bit of background before the graphics get involved, it was clearly evident that Villa’s midfield were operating deeper than they perhaps could have been. Given that the team started with Darren Bent up front, this choice left the striker isolated meaning that he had few touches of the ball given his style of play. The bottom line there is simple – Bent can’t score if he doesn’t have the ball.

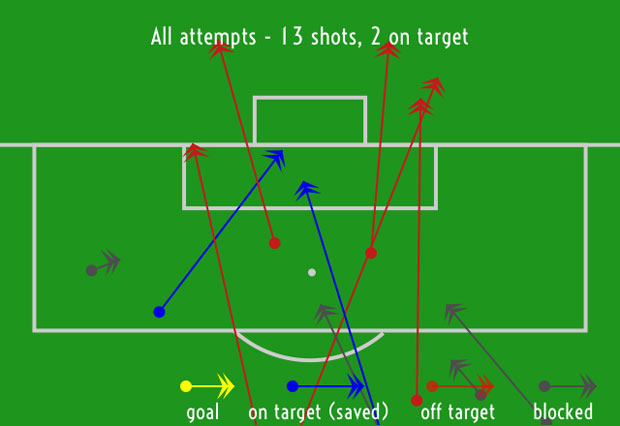

Make no doubt about it, Villa’s team were passing the ball far better but passing alone is far from sufficient to win games. Obvious as it is, you only win games by scoring goals, and you only score goals from creating chances. Villa had more shots than West Ham (13 compared to West Ham’s 8) but had fewer on target.

The graphic below illustrates Villa’s shots on goal. As you’ll probably notice, not a single one of those shots was in the six yard box and only four of Villa’s 15 were in the penalty area.

What does this matter I hear you ask? Bent is a poacher, and his goals he scores largely come from within the penalty area and, more often than not, from the six yard box. If Bent hasn’t taken a shot in the area he scores goals for, he is unlikely to provide the necessary goals.

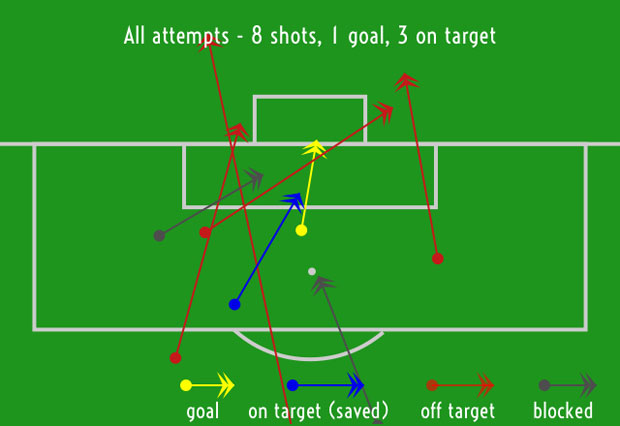

Compare that to West Ham who had five of their eight shots inside the area, with Kevin Nolan goal coming from just outside the six yard area. Despite the fact that the defence became rather static making calls for offside, something originally backed up by the linesman, the goal went in and Villa were 1-0 down. Below is the breakdown of West Ham’s shots for your reference:

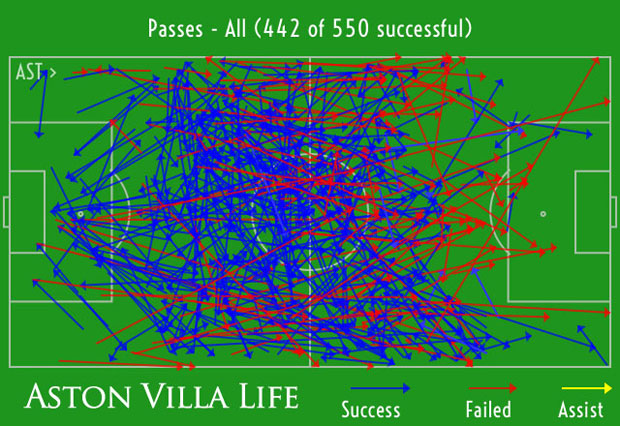

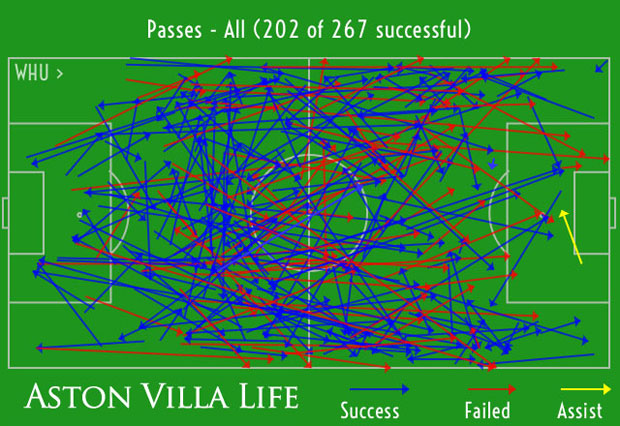

Moving on from shots to passes, Villa exhibited a clear domination of the overall passing stats with a massive 550 total passes compared to West Ham’s 267. As I wrote in my pieces over the weekend, passing alone won’t win you games. We saw in the Gerard Houllier era that you can pass and pass but still falter in result terms. I’m not suggesting that Paul Lambert’s first season will equate to what Houllier achieved with Villa, but the point is there.

Below are Villa’s total passing statistics illustrating a strong focus on successful passes (marked in blue) down the right hand side of the pitch. Comparatively speaking, left sides passes did not succeed as often:

Compare and contrast this to West Ham’s overall passing that looked comparatively sparse when viewed against Villa’s:

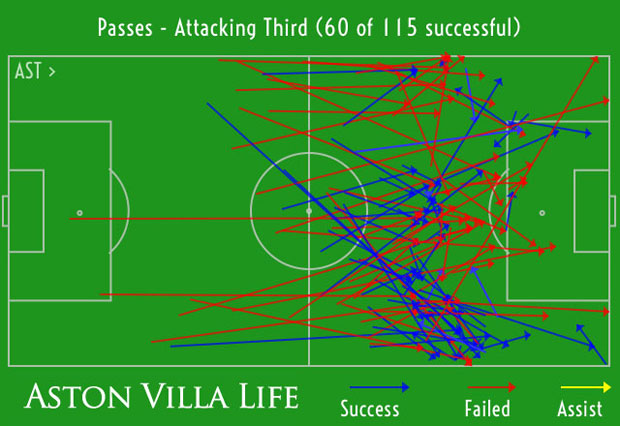

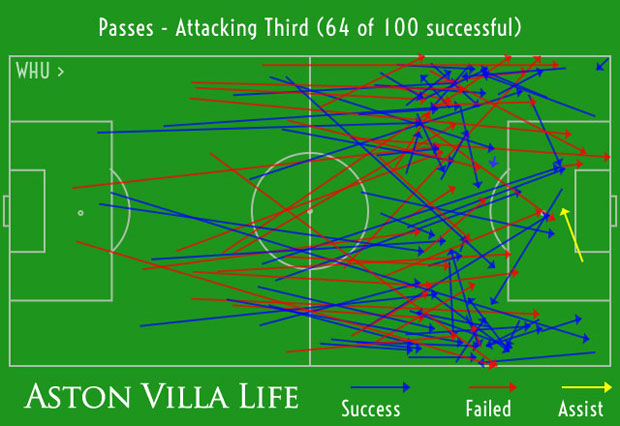

However, these graphics only show half of the story – we need to look deeper into attacking third passes to see why Villa were unable to win the game. When we take a direct look at solely attacking third passes, the difference between the teams is far closer with Villa having 115 passes compared to West Ham’s 100.

When you consider that Villa had made a full 283 passes more than West Ham, the fact that only fifteen were in attacking areas showed that, by exclusion, the other 268 passes were in the first two thirds of the pitch.

Below are Villa’s and West Ham’s attacking third passes for reference. You will notice that Villa had more attacks going through the right than the left illustrating that Matt Lowton had a comparatively better game than young Nathan Baker:

Nobody can doubt the benefit of keeping possession in terms of winning games. If you have the ball, you can score. If you score, you can win. By obvious comparison, if you don’t have the ball, you can’t score. Passing and holding the ball is a part of what can make a team good but it is far from the full answer.

Villa dominated possession by a significant amount with 65.8% possession to West Ham’s 34.2%. Again, this statistic is disingenuous because when you look at the more relevant territory stat, ie how much of the pitch each team controlled, Villa actually came out second best with only 45.5% territory to West Ham’s 54.5%.

So if Villa were mostly in their own half, is it any wonder that the team lost? If Villa left large gaps between the midfield and Bent, and these gaps meant Villa did not score, it illustrates two individual solutions to the problem.

The first is that the midfield must push up to close the gap between Bent and the other attacking players. It was perfectly understandable as to why Villa sat deep – a combination of the fact the team were playing away and that the midfield were looking to shield the defence – but future games, particularly at home, must involve more risk taking.

The second option is that Bent (or whoever is playing striker in a similar formation) must come deeper to receive the ball. It is no good having a series of fluid ten yard passes around the midfield if the last pass has to be a long punt. All that does is give the team a lot of possession but no penetration in terms of scoring opportunities.

There is no doubt that Lambert will scrutinise the result and demand more from his team when they start their home campaign against Everton this coming Saturday. The only question remains is what do you think the manager should do? Should our midfield push up? Should our striker (or strikers) come deep to receive the ball? A combination of the two?

It’s over to you – let me know your thoughts and I hope you enjoyed this Talk Tactics article.

*** Statistical passing images courtesy of FourFourTwo’s Stat Zone app with data provided by Opta. Available for free download from the App Store on iPhone ***

Podcast: Play in new window | Download